|

| A 1901 photo of a a survey geologist in Nome |

(Hickel, Walter J. Olds, Glenn A. Smith, Thomas E. State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys. July 1992)

The region consists of Quaternary coastal and glacial sand and gravel deposits. The sands are re-worked clastics derived form Paleozoic sedimentary and metasedimentary rocks that form the highlands of Anvil Mountain and North Newton Peak north of Nome. At various undisturbed locations, surface water collects above the shallow permafrost and has contributed to the wet tundra and wet near-surface conditions.

Gold Rush 1898-1909:

|

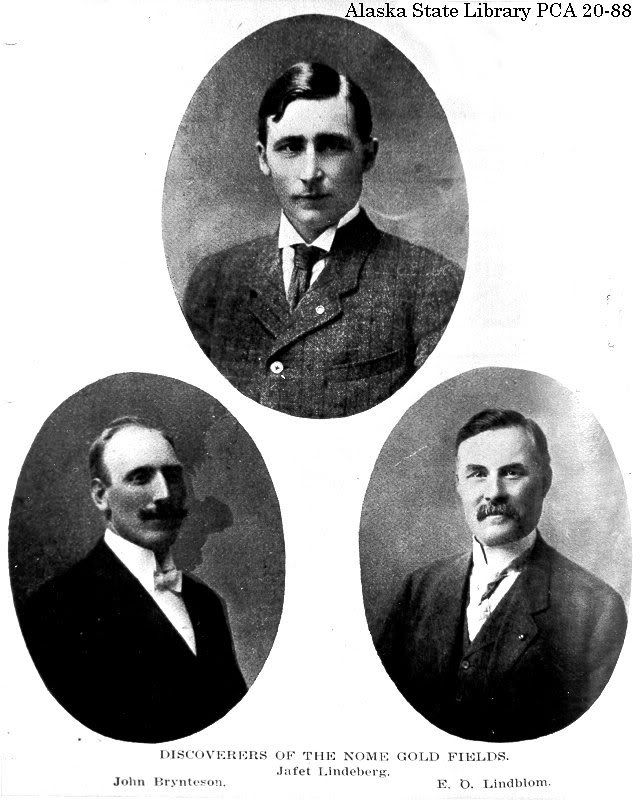

| "Three Lucky Swedes" |

| Tents, boats, and people in Nome 1899 |

|

| Elizabeth Robins |

When Elizabeth Robins, a British newspaper correspondent and actress, arrived in Nome, she described the scene on the beach:

The tents come down the shingle in some cases within a few feet of where surf is breaking.

The space remaining is already piled with freight--food supplies barrels of beer and whiskey, bags of beans and flour higher than my head, lumber, acres of it, extending beyond the tents and up on the tundra, furniture, bedding, pots and pans, engines and boilers, Klondike Thawers, centrifugal pumps, pipe and hose-fittings, gold rockers, sides of bacon, blankets, smart portmanteaux and ancient sea chests--as odd a conglomeration as ever an eye rested on.

I thought this gave a great visual of what things looked like and what kind of things were going on in Nome at this time.

| Front St. Business Establishments Nome, AK ca. 1900 |

By 1905, Nome had schools, churches, and a newspaper. Among the variety of businesses were at least 20 drinking establishments, 16 lawyers, 11 physicians, 12 general merchandise stores, 4 real estate offices, 4 drug stores, 3 watchmakers, 3 fruit and cigar stores, 5 laundries, 4 bath houses, and one massage artist.

By 1909, the population had dropped to 2,600. The rush was over but mining for gold there still takes place today. Total gold production for the Nome district has been at least 3.6 million ounces.

The Natives had a major loss in this gold rush. Mining claims could only be staked by citizens and since Natives were considered to be uncivilized, they could not get citizenship. Because of the thousands of people coming to Nome, the number of moose and caribou as well as smaller game was drastically reduced. Mining also resulted in the destruction of salmon streams. Drinking and disease were also introduced to the Natives.

I had the chance to meet someone in Nome who's family came to Nome for the Gold Rush. His name is Larry and he took me and my friends on an Arctic Cat ride out to Safety. His great grandparents came to Nome and staked claims. The claims are still in the family and he said they go out there every once in a while and do a little digging. He also said that he plans on staying out on the property more regularly and start up the whole process again on a small scale.

Serum Run 1925:

|

| Dr. Curtis Welch |

The only two choices of delivery were by plane or dog sled. The only bush planes available had open cockpits and water-cooled engines. Flying at fifty below was too big of a risk not only for the pilots, but for the serum as well. A vote was taken and the dogsled relay was unanimous. Only expert dogsled racers could make the journey because of the worst winter conditions they had since 1905. Mail carriers were chosen to deliver the serum because of their vast knowledge of the trail and expertise of traveling. All together there were twenty men and 150 dogs. The drivers would have to cover over 674 miles to deliver the serum to Nome.

|

| Route to Nome |

A radio signal went out and carried for miles across the frozen tundra. Nome was urgently calling for a diphtheria serum. Seattle responded and said they had fresh serum and they had a plane standing by to fly to Nome. However, because of the bad winter weather, the plane wasn’t able to fly to Nome. Anchorage had received 300,000 units of serum. They would be able to transport the package to Nenana by the Alaska Railroad and then have a dog team take it the rest of the way. On January 27, the race to get the serum to Nome began.

All mushers had a hard time getting through the rough winter weather. The serum finally made it to Gunnar Kaasen who traveled the last leg of the race. The famous dog, Balto, was the lead dog. Kassen had made it to the last stop, Safety, and he found the next driver sleeping. He was only 21 miles outside of Nome and his dog team was running nicely so he decided to keep going to Nome.

|

| Kaasen and Balto |

This site gives a nice timeline of the events carried out.

WWII 1941:

Nome was home to an airfield during World War II. Thousands of aircraft, headed for the Western Front, landed in Nome where U.S. Aviators handed over the planes to Russian pilots to fly them through Siberia to fight the Nazis for the Lend-Lease Program.

The Lend-Lease Act of 1941 premitted the United States to lend or lease supplies to allies fighting aggression. Payment could be in kind, in property, or in any benefit accepted by the United States, and payment could be deferred to a later date.

|

| Northwest Staging Route |

|

| Russian Military in Nome, AK |

The Civil Aeronautics Administration began construction of the Nome airfield in 1941, and the Army soon assumed responsibility for what was called Marks Air Force Base. The intent of this was to protect the northwest coast of Alaska from attack by the Japanese. Military planes based in Nome provided that protection throughout the war. At different times, B-18 and B-24D bombers and P-39F fighters provided the defense of Nome and northwest coast. Lend Lease became the main activity at Marks Field. Signs of military presence include the numerous Quonset huts.

Source:

Millbrook, Anne. Lend-Lease Air Route of World War II. Nome Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Iditarod 1970:

|

| Joe Reddington |

Reddington had two main reasons for creating this race: to save the sled dog culture and Alaskan huskies, which were being phased out by snow machines; and to preserve the historical Iditarod Trail between Seward and Nome. The race is a reconstruction of the freight route to Nome and commemorates the part that sled dogs played in the settlement of Alaska. The checkpoints were set up along the trail for the mushers to stop at, much like the freight mushers did eighty years ago. The Iditarod is something that most of these villages look forward to all year.

|

| Winner's Trophy |

|

| Iditarod Trail |

The trail is impassable during the spring, summer and fall and is far from straight. The race is a total of about 1,049 (the 49 being symbolic to the 49th state) miles and only about 650 miles by airplane. The trail was routed to wind through a number of towns and villages missed by the original trail. There is a northern route for even-numbered years and a southern route for odd numbered years.

|

| Me and Dallas Seavey |

Fuel Predicament: 2012

|

| Redna and U.S. Coast Guard |

Back in November of 2011, Nome was supposed to get their last deliver of fuel for the winter. However, because of an early storm this winter, the shipping lanes were frozen preventing the shipment of fuel to reach Nome. After November, the next scheduled delivery of fuel was not possible until March at the earliest. There was no way that Nome was going to be able to survive through the winter.

Ideas about possible ways to get Nome their much needed fuel began to surface. They talked about flying the fuel in but decided against it because they would only be able to fly in 5,000 gallons at a time when they needed over 1 million gallons.

| Sitnasuak Native Corporation |

|

| Hoses used to transfer fuel |

Extra:

This video was very interesting to watch. It has a lot of history and modern day Nome happenings and area villages. I was just there for the end of the Iditarod back in March. It was interesting to see what it looks like in the summer. I was happy to see Tom in the video. He works at the Safety Roadhouse and we met him when we were on our Artic Cat tour.

Cause-Effect Statements:

1. The city of Nome was established because of the "Three Lucky Swedes" who discovered gold in the Seward Peninsula in 1898, and as a result, word spread and droves of people in search of finding their own fortune came to Nome in the early 1900's, significantly increasing its population.

2. Because of the population boom in the early 1900's, Nome Natives were exposed to new diseases like diphtheria, which became an epidemic in 1924 and originated in the Native village of Holy Cross.

3. During WW II, The Lend-Lease Act of 1941 required an airstrip to be constructed in Nome called Marks Field which is still used today on a regular basis; Alaska Airlines flies in and out of Nome twice daily.